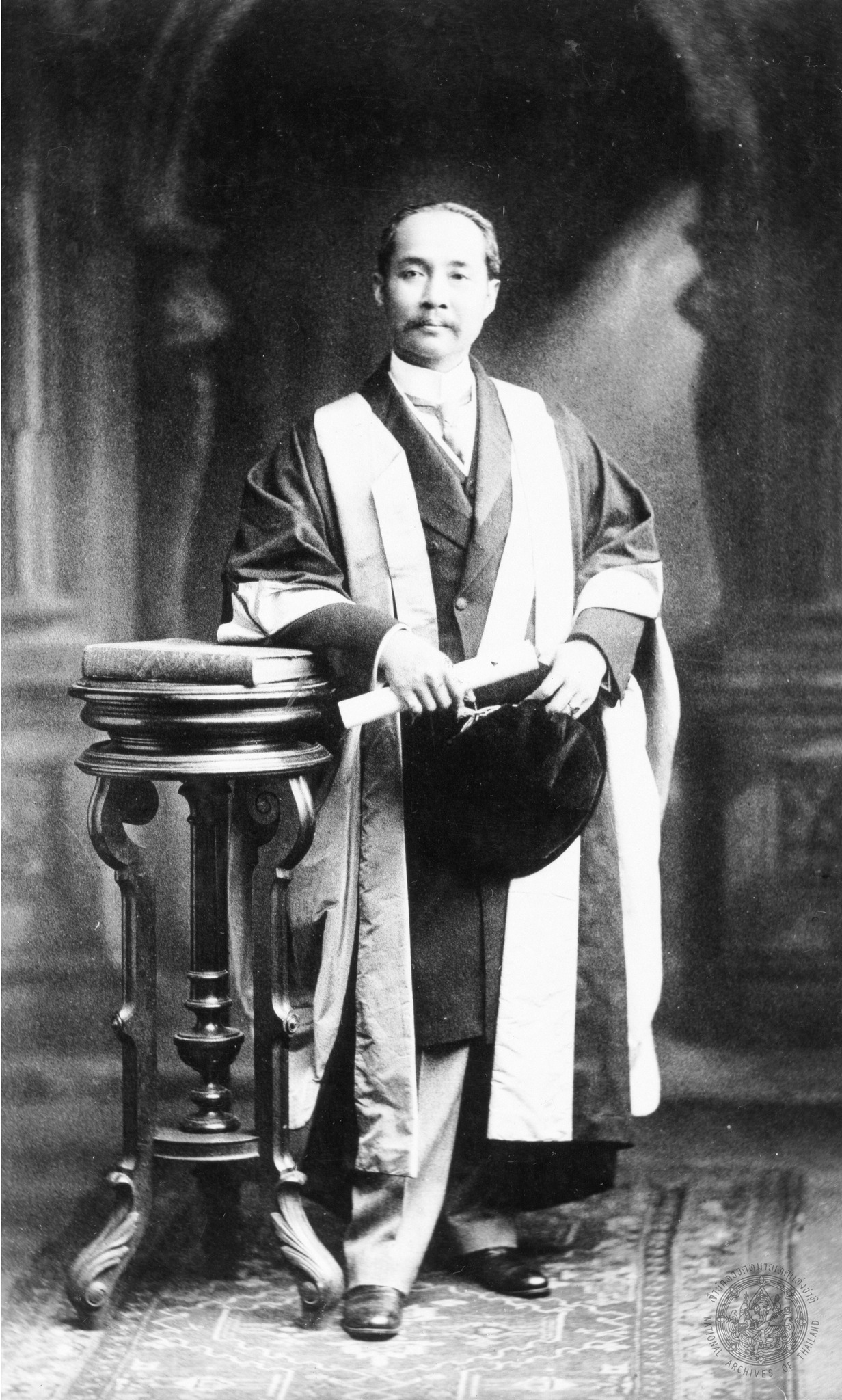

The construction of Charoen Krung Road, also known by Western residents as “New Road,” symbolised Siam’s opening to Western influence following the Bowring Treaty. As foreign merchants and residents increased, King Mongkut initiated the road project to facilitate land transportation—an innovation at the time. The road was designed by Henry Alabaster. Built in two phases, the outer section connected Saphan Lek to Bang Kholaem, and the inner section linked Wat Pho to the outer segment. The road paralleled the river, shaping the city’s economic growth corridor. Shop houses were introduced along its length, based on designs from Singapore, setting a new model for urban commerce.

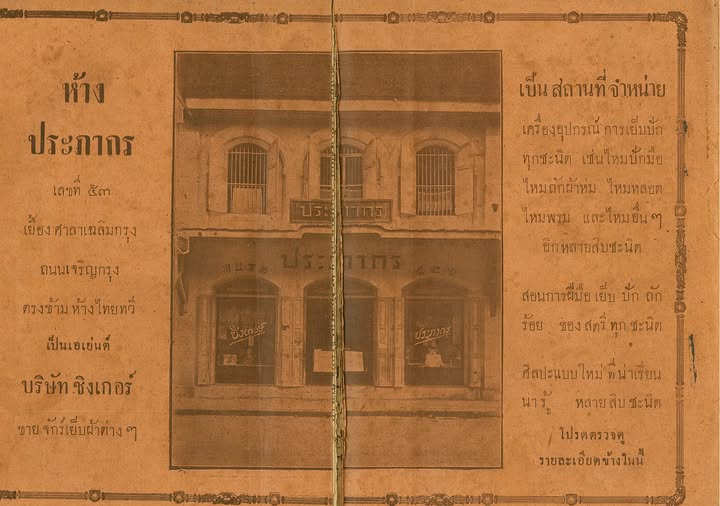

In addition, King Mongkut (King Rama IV) commissioned Chao Phraya Si Suriyawong (Chuang Bunnag) to travel to Singapore to study the design of shop houses commonly used in British colonial cities. These architectural forms were then adapted for use along Charoen Krung Road, establishing a new standard for urban commercial buildings in Bangkok. The King granted plots of land along the road to his sons and daughters, allowing them to construct and rent out shop houses for trade. The road became a vital artery of reform, and served the growing middle class, connected civic institutions, and accommodated modern infrastructure such as waterworks, electricity, schools, hospitals, and later, electric trams. It reflected Siam’s effort to modernise and maintain sovereignty during the height of European imperialism.

During the reign of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), Charoen Krung Road was regarded as a prime commercial district in Bangkok. It became a hub for foreign merchants and trading houses, many of which established their premises along this bustling thoroughfare. Among them was Société Anonyme Belge, a Belgian-owned department store recognised as one of the first to offer imported European goods in Siam. Another notable establishment was J.R. André, which specialised in procuring a wide range of luxury items from abroad—including jewellery and precious stones—and also served as an official distributor for Opel automobiles.

The expansion continued under King Vajiravudh (King Rama VI), who tackled the area’s urban congestion and frequent fires by extending connecting roads like Pathum Khongkha, Phadung Dao, and Bamrung Rat. This urban planning shift prompted residents to move towards Silom and Sathorn, where space allowed further development. In 1925, the state introduced a tramline from Silom to Pratunam, further drawing attention away from Charoen Krung.

During the reign of King Prajadhipok (King Rama VII), land values in Bangkok rose significantly. Commercial buildings and land were increasingly utilised for business purposes, driving the continuous growth of commercial districts along Charoen Krung Road. As traffic congestion on the road intensified, new roads were constructed to alleviate the problem. At the same time, this urban expansion pushed many residents to relocate to areas outside the city centre. The neighbourhood gradually lost its centrality as Bangkok’s commercial hub, especially after the construction of Phra Phuttha Yodfa Bridge (Memorial Bridge) in 1932 under King Prajadhipok (King Rama VII), which better connected Thonburi and Phra Nakhon without reliance on ferries.

During World War II, the district witnessed a major transformation. As Thailand allied with Japan and declared war on the Allies, many Western-owned businesses along Charoen Krung were seized or shut down. This accelerated the shift of commercial activities to Silom Road, signalling the decline of Charoen Krung as Bangkok’s premier business zone and the rise of a new urban core.