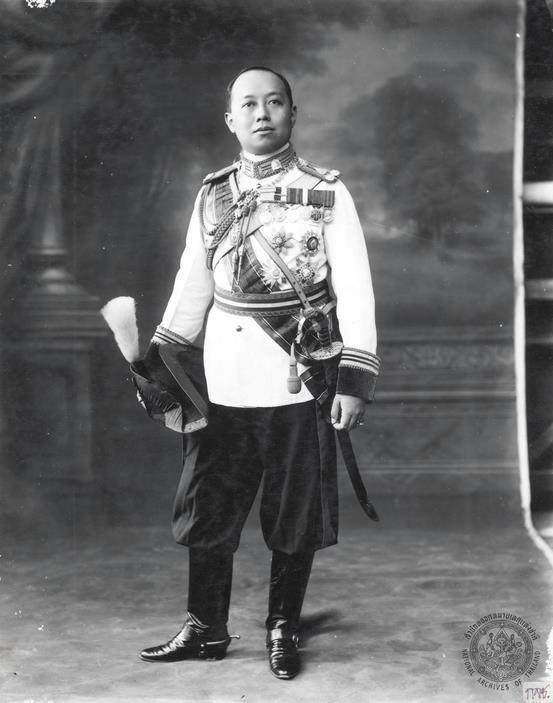

Suankularb Wittayalai School began in the royal Suankularb Palace compound when Prince Damrong Rajanubhab requested that the palace buildings be used for a school. King Chulalongkorn (King Rama V) granted permission, and the school became known as “Phra Tamnak Suankularb School”.

In 1884, the school was transformed from an institution for royal pages into a Civil Service School, with classes divided into junior, middle and senior levels. As the number of students continued to increase, the school had to move several times. In 1893 it relocated from the Grand Palace to new premises at Wat Mahathat and the Wang Na (Front Palace), where it became known as Suankularb Wang Na. A further move followed in 1905 to the Maen Narumit Building at Wat Thepsirin, after which it was commonly referred to as Suankularb English Thepsirin. Finally, in 1910, the school was merged with Rajaburana School and given the new name Suankularb Wittayalai School, marking the beginning of a more modern phase in its development.

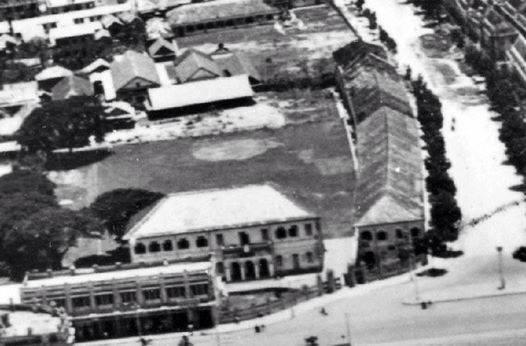

That same year, construction began on a new European-style neoclassical building – later famously known as the Long Classroom Block (Tuk Yao). It was the school’s first purpose-built teaching facility, reflecting the architectural tastes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The building contract was signed by Luang Rachaya Sathok, the makkanayok (lay head of temple affairs) of Wat Ratchaburana Ratchaworawihan, was the signatory to the employment contract., and the work was undertaken by contractor Mr. Eng Liang Yong. Upon its completion in 1911, an official opening ceremony and merit-making ceremony were held on 24 June 1911, presided over by Chao Phraya Phrasadet Surenthra Thibodi (M.R. Pia Malakul), then Minister of Public Instruction.

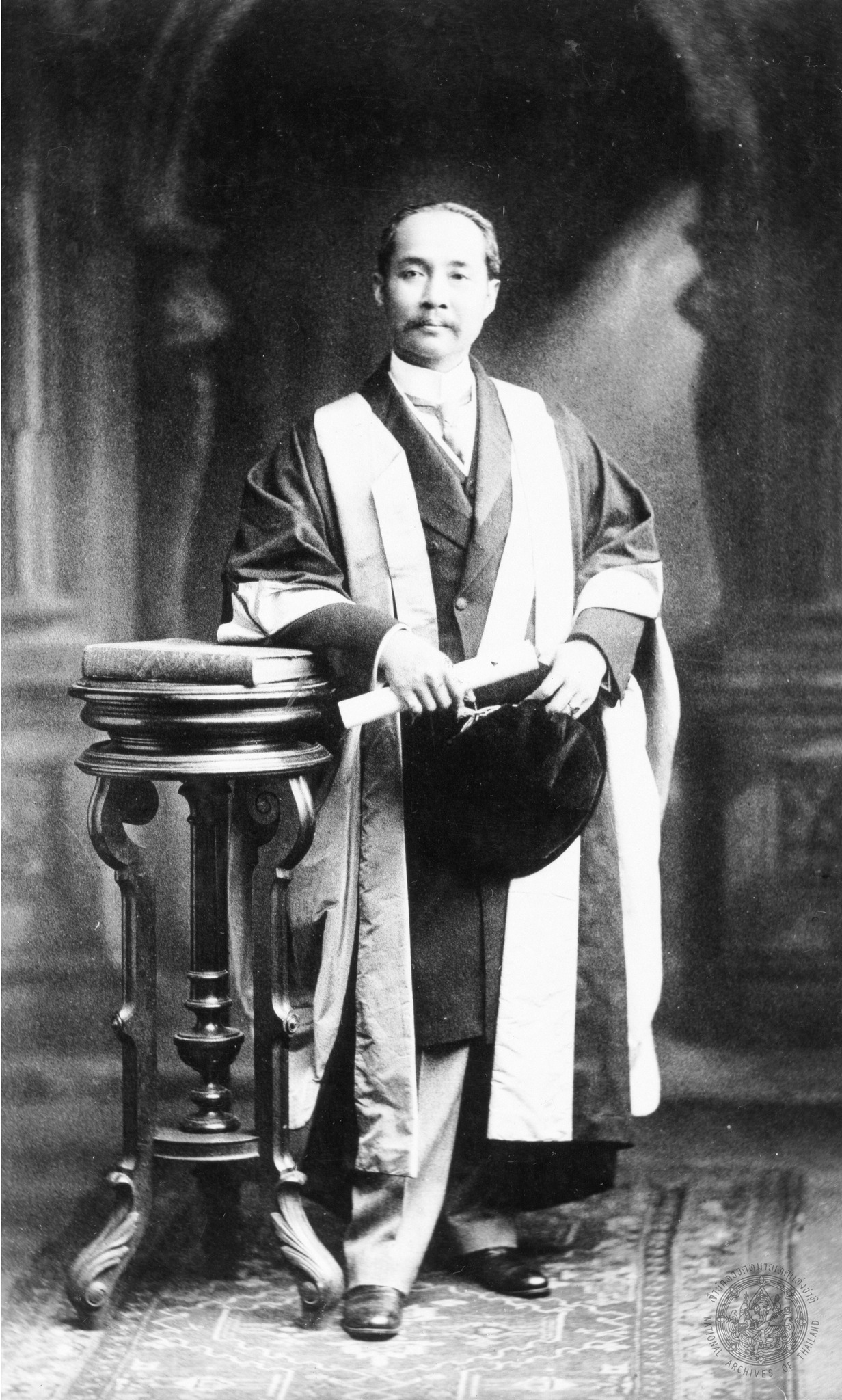

Suankularb Wittayalai School became the first royal school in Siam and laid the foundation for modern education in the kingdom. King Chulalongkorn recognised that to modernise Siam rapidly in the face of colonial pressures, the people of the nation – including royals, nobles, officials and commoners – needed to be literate, disciplined and knowledgeable about science and the modern world. Traditional temple-based education was no longer sufficient for national survival and progress.

The new school system introduced during this period established formal curricula, timetabled teaching, examinations, scholarships for study abroad, and the training of capable individuals who would return to serve as the backbone of the country’s administration and development. Suankularb Wittayalai was therefore more than just a school: it was a symbol of the nation’s first steps towards modernisation through education.