This article is adapted from Museum in Focus, a talk series developed by Museum Siam to create a public space for learning about “urban heritage” in a broader and more contemporary sense. Here, urban heritage does not refer only to old buildings, historic districts, or old maps. It also includes infrastructures and systems that shape everyday urban life—energy, transportation, rail systems, and even green spaces such as public parks. All these elements tell powerful stories about how Thai society has changed over time.

The first event of the series took place on 29 November 2025 at Museum Siam’s Multipurpose Hall, followed by a guided visit to the Thai Electricity Museum at the former Wat Liab power station. Under the theme “When Light Changed Society,” participants explored how electricity was not simply a technology that illuminated the city, but a driving force that transformed lifestyles, urban culture, and the idea of modernity in Thailand. Seeing electricity in this way becomes a new way of “reading the city” — understanding energy as an active part of living urban heritage, shaping the future of modern Bangkok.

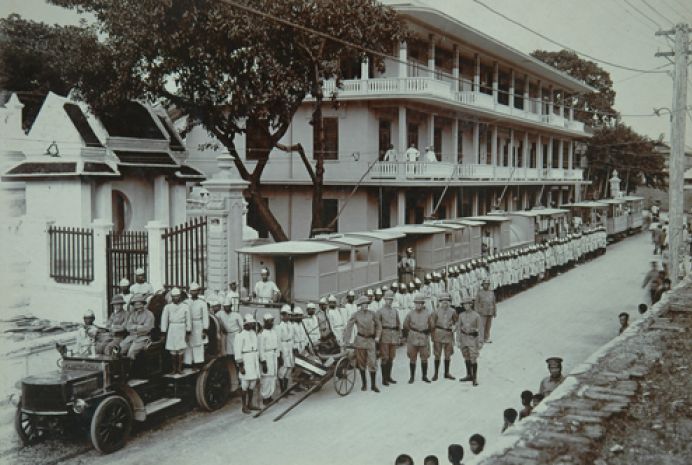

A panel discussion during Museum in Focus #1: When Light Changed Society, featuring speakers seated from left to right: Kirin Thummanon, Lt. Krisada Khongyoo, Weerayut Pisalee, Tratsa Maneechote, Wattanyu Thephatti, and Khasara Mukdawijitra (moderator). The projected image behind the panel shows the early construction of Building 1, the historic structure later restored and transformed into MEA SPARK, Thailand’s Electricity Museum.

Image source: Thanyawiwatkul, Y. (2025, November 29). Panel discussion at Museum in Focus #1, Museum Siam [Personal photograph]. National Discovery Museum Institute (Museum Siam).

The First Light of Siam

The session opened with a presentation by Tratsa Maneechote, Director of Communication Strategy at the Metropolitan Electricity Authority (MEA). She took the audience back to 1884, when Siam first encountered electricity during the reign of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V). Electricity was initially tested at the Front Palace by Chaophraya Surasakmontri (Choem Saengchuto), who pioneered early generators and wiring systems. This “first light” amazed nobles and the public alike. When the news reached the King, he ordered electric lighting to be installed in the Grand Palace. From there, electric lights spread gradually to royal residences and then into the city—marking a significant turning point in Siam’s entry into modern life.

From these early trials, Siam began developing electricity into a more systematic service. A Danish company received the concession to generate electricity for the electric tram system and built a permanent power plant at Wat Liab. A stable power source not only expanded access to electricity but also reshaped transportation, the economy, and urban management in the late 19th century. In 1914, another state-owned power plant was established at Samsen. The two operations were later merged and evolved into the “Bangkok Electricity Authority,” which eventually became today’s Metropolitan Electricity Authority (MEA) serving Bangkok, Samut Prakan, and Nonthaburi.

During this period, the Siam Electricity Company—also run by Danish figures such as Aage Westenholz and Andreas du Plessis de Richelieu—played an essential role. Richelieu, who held the concession for electric tramways, helped establish the permanent Wat Liab power station. Reliable electricity did not only increase convenience but fundamentally changed Bangkok’s urban landscape, mobility, and economy. With the establishment of the Samsen power plant and the later merger of services, the city moved steadily toward having a unified, modern electrical system.

Tratsa emphasised that electricity was not just a new technology—it deeply transformed life and the urban environment. Street lighting made the city safer at night, extended economic activities, and allowed new forms of entertainment to flourish. Tramlines connected districts more efficiently, allowing mobility between neighbourhoods. Importantly, she highlighted MEA’s intention to tell the story of electricity as an urban narrative—not merely an engineering history. This vision led to the creation of the Thai Electricity Museum (MEA SPARK), designed to let visitors experience historical events and personal memories that shaped Thailand’s electrical heritage.

Electricity and the Making of a Modern City

The next speaker, Weerayut Pisalee, a social studies teacher from Mahidol Wittayanusorn School, invited the audience to see electricity not only as a technology but as a force that shaped cities and people’s experiences. He discussed how city landscapes changed, how night-time life emerged, and how urban celebrations evolved during periods of transition.

He began by showing how electric lighting first appeared on major roads and important neighbourhoods—Charoen Krung Road, Chakrabongse Road, and areas around Wat Suthat. By the late 19th century, lampposts had become part of the city’s visual identity. They were not just public utilities but symbols of civilisation, signalling that Bangkok was entering the modern era.

Weerayut then turned to “night-time life,” using photographs, diaries, and writings of the time. With electric lighting, people began walking the streets after dark, new social activities emerged, and places that once fell silent after sunset became lively. Electricity changed how people related to the city—emotionally and experientially—reshaping their sense of public space.

He also discussed how lighting became part of the city’s “culture of celebration.” In the 1930s, festivals and events—such as those held at the Royal Bangkok Sports Club—used decorative lighting to create atmosphere and excitement. Light was no longer just functional but emotional, creating shared experiences and a sense of modernity.

By the end of his talk, Weerayut highlighted how electricity created Bangkok’s early “night districts”—Sampeng, Yaowarat, Ratchawong, Bang Rak, Bang Lamphu, and Saphan Phut. These areas became centres of commerce, entertainment, and social interaction. Night-time economies slowly took shape, driven by electricity as an enabling force for new social, cultural, and economic possibilities.

Electricity in the Era of Sustainability

The final speaker of the session, Lt. Krisada Khongyoo from the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), connected the history of Thai electricity to contemporary energy challenges. He explained that while electricity was once a symbol of early civilisation, today it is an essential foundation of modern cities. Economic growth, transportation, digital technology, and public services all depend on a stable and reliable energy system.

He illustrated this with everyday examples—smartphones, computers, communication networks, and the rise of electric vehicles. Modern life depends so heavily on electricity that most people rarely stop to consider its importance. What has changed is not only the growing demand for electricity but the increasing complexity of how cities rely on it.

Krisada emphasised that Thailand now faces a major challenge: transitioning to clean energy and a low-carbon society, aligned with both national and global goals. Modern energy systems must balance security and sustainability, making energy not just a technological issue but one deeply connected to people’s futures and the environment.

The first part of the event painted a clear picture: electricity did not only change the city’s physical landscape but also shaped rhythms of life, urban culture, and ideas of modern civilisation. Tratsa introduced the historical beginnings, Weerayut showed how light reshaped urban experience and night-time life, and Krisada connected these stories to the challenges of today’s energy systems.

The second part of the programme invited participants to explore the historic Building 1, the early power station at Wat Liab. It raised an important question: how can a site that embodies both technological heritage and collective memory be revitalised to tell the story of Thailand’s electrical history today? This led into a discussion about the restoration of Building 1 and how its past can be brought back to life as a contemporary museum.

Bringing an Old Building Back to Life

Wattanyu Tephatti, Managing Director of Kudakarn Co., Ltd. and conservation architect for Building 1 at the Wat Liab power station site, explained that this structure survived the Second World War and is one of the earliest reinforced-concrete buildings in Thailand. It is therefore valuable both historically and architecturally. At the same time, turning it into a functioning museum has been full of challenges. Parts of the structure had subsided and tilted, many areas no longer met modern safety standards, and the building systems did not comply with current regulations. The restoration had to start from a deep understanding of the building’s past, while also planning carefully for its future use.

During the survey, the team discovered important traces that revealed hidden beauty and stories—for example, mural paintings along the main staircase. These suggested that Italian craftsmen may once have been involved in the interior decoration. Although much of the painting has faded, the remains confirm that Building 1 is more than an old shell. It is a storehouse of memories, combining early modern architecture with artistic details. The conservation team therefore tried to preserve as many original elements as possible, especially the walls, window openings, and old materials that can “tell their own stories”.

The structural work was equally delicate. Wattanyu explained that the team had to jack up the entire building by more than one metre to correct the subsidence and protect it from future flooding. They also strengthened the structure to stop further tilting and opened up the staircase hall to function safely as a public building. At the same time, they added a new extension at the rear to house toilets, a reception area, fire escapes, and updated building systems. The extension design also had to respect the view of Wat Liab’s historic prang, an important landmark of the area, so that the new volume would not dominate or block it. Every design decision had to find a balance between safety, practical use, and cultural value.

The biggest challenge was transforming Building 1 from a former office into a contemporary museum within a space full of physical constraints. The original rooms were small and had limited load-bearing capacity. The design team therefore had to manage the space very carefully—preserving the building’s original atmosphere while creating enough room for visitors to learn about the history of electricity. In this sense, the project is not only about repairing a structure. It is about bringing Thailand’s electrical heritage back to life so that it can once again tell stories about the city in a contemporary and accessible way.

Designing Stories Inside an Old Building

For exhibition designer Kirin Thummanon from Plan Motif Co., Ltd., working in Building 1 was not just about displaying the history of electricity. It meant interpreting “a hundred-year story” so that it could fit into a small, structurally limited historic space. He explained that the main task was to cover everything from the era before electricity to the future of energy. The exhibition had to respect the original walls and avoid adding heavy showcases that would overload the floors. In short, the design had to honour the restored architecture. The displays therefore had to remain “light”—both in physical weight and in visual treatment—while still connecting historical facts into a coherent story within a building that could only be altered in small ways.

Kirin designed the exhibition route to begin on the third floor, where visitors are introduced to the Wat Liab neighbourhood before the age of electricity. From there, the story moves through key milestones in Thai electrical history: the first appearance of electric light, the establishment of electricity services, and the gradual brightening of the city. The layout follows a clear timeline from past to present. Graphics, wall-mounted models, and a variety of media were used to reduce the need for heavy objects on the fragile floors. Some rooms were turned into immersive experiences—for example, a space that recreates the feeling of a night-time district brought to life by electric light.

Exhibition design in an old building must also follow strict safety regulations. Some rooms had to function as fire exits and therefore could not use flammable materials. Other spaces required careful control of natural light because the original openings could not be changed. Kirin chose to “attach” as much as possible to the existing structure—using walls as load-bearing surfaces, keeping original room sizes, and relying on lightweight materials that match the character of the building. He sees this not as a limitation but as an opportunity for visitors to experience the authentic atmosphere of an old industrial building.

At the end of his talk, Kirin reflected that the exhibition at MEA SPARK is a collaboration between “building, objects, and stories”. Many artefacts had been kept for decades in various MEA facilities before being gathered in one place and reinterpreted for this exhibition. He suggested that the museum should also create space for people to share their memories—such as seeing electric light for the first time. In this way, the building itself becomes part of the narrative. The result is a story in which the history of energy and the life of the city are closely intertwined.

The first Museum in Focus event showed that the history of electricity is not just about technological progress. It is also about people, cities, and long-term social change. Tratsa Maneechote, Weerayut Pisalee, Lt. Krisada Khongyoo, Wattanyu Tephatti, and Kirin Thummanon together opened up new perspectives on how energy has shaped everyday life, urban culture, and ideas of modernity. At the same time, they highlighted what it means to preserve electrical heritage—through technology, building conservation, and contemporary exhibition design.

After the discussion, participants continued to the Thai Electricity Museum (MEA SPARK) to experience the site in person—a place that is both an industrial heritage landmark and a living learning space. Walking through Building 1, they could see the traces of history that Wattanyu had described, while hearing more about the restoration process and the creation of the exhibition on site.

This programme offered a layered way of learning about “urban heritage”: from the first electric light in Siam, to Bangkok’s night-time life and the challenges of modern energy, and finally to a historic building brought back to life as a museum. It made clear that old buildings can tell powerful stories about the city when they are carefully cared for and when their historical value is held in balance with contemporary ways of interpreting the past.

- Speakers:

- Tratsa Maneechote — Metropolitan Electricity Authority

- Weerayut Pisalee — Mahidol Wittayanusorn School

- Lt. Krisada Khongyoo — Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand

- Wattanyu Tephatti — Kudakarn Co., Ltd.

- Kirin Thummanon — Plan Motif Co., Ltd.